WASHINGTON – After four years of warnings and preparations, the 2020 presidential election did not see a repeat of 2016, when intelligence officials concluded Russia meddled using a combination of cyberattacks and influence operations.

But according to current and former U.S. intelligence officials, as well as analysts, the good news ends there.

The Russians, they warn, have been busy laying the foundation for future success.

Instead of relying on troll farms and fake social media accounts to try to sway the thoughts and opinions of American voters, they warn the Kremlin’s influence peddlers have instead gained a new foothold, establishing themselves as part of the United States’s news and social media ecosystem, ingratiating themselves to U.S. audiences on the far right and the far left.

“A lot of these campaigns are getting engagement in the millions,” Evanna Hu, chief executive officer of Omelas, told VOA. “They are pretty good at inducing the type of sentiment, a negative sentiment or a positive sentiment in the audience, from their posts.”

Omelas, a Washington-based firm that tracks online extremism for defense contractors, has been studying Russian content across 11 social media platforms and hundreds of RSS feeds in multiple languages, collecting 1.2 million posts in a 90-day period surrounding the November 3 election.

It found the most prolific Russian outlets included state-backed media outlets like RT, Sputnik, TASS and Izvestia TV.

“We only look at active engagements, so you have to physically click on something or retweet it,” said Hu, admitting that the estimate for the millions of engagements is still “pretty rough.”

Also, Omelas determined that only about 20% of the posts pumped out by Russia’s propaganda and influence machine are in English. Forty percent of the content is in Russian, with the rest going out in Spanish, Arabic, Turkish and a handful of other languages.

Russian-backed media

U.S. officials have been reluctant to speak publicly about the impact these efforts have had on American citizens, in part because there is no easy way to measure the effect.

After the 2016 election, for example, intelligence officials repeatedly said while they were able to conclude Russian efforts expressed a preference for then-candidate Donald Trump, they could not say whether any Americans voted differently as a result.

Still, multiple officials speaking to VOA on the condition of anonymity given the sensitivity of the subject said it was unlikely that Russia would continue to spend money on these media ventures if the influence operations were not producing results.

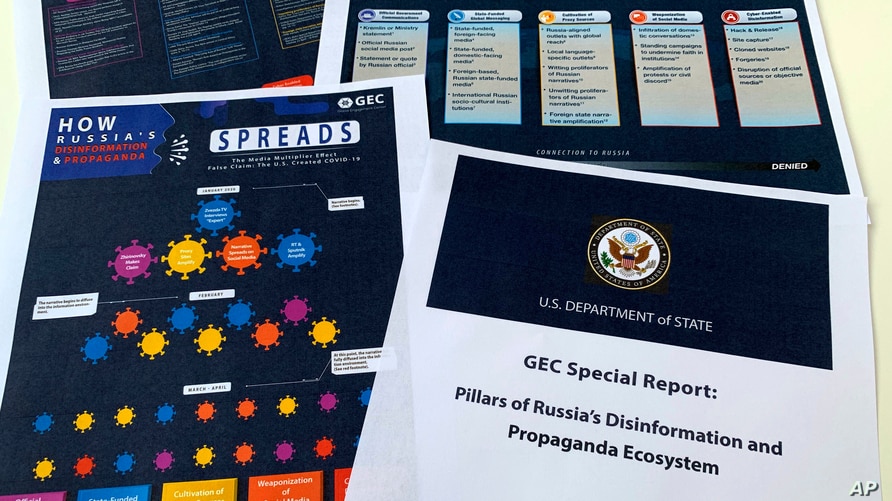

An August 2020 report by the State Department’s Global Engagement Center, while not sharing a figure, concluded Moscow “invests massively in its propaganda channels, its intelligence services and its proxies.”

U.S. election security officials have likewise repeatedly voiced concerns about Russia’s efforts to stake out space in the news and social media ecosystem.

“I’m telling you right now, if it comes from something tied back to the Kremlin, like RT or Sputnik or Ruptly, question the intent,” Christopher Krebs, the former director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, told a cybersecurity summit in September. “What are they trying to get you to do? Odds are, it’s not a good thing.”

Senior CISA officials again called out Russian-backed media while briefing reporters on Election Day (November 3), begging Americans to treat any information coming from Russian-linked sources with a “hefty, hefty, hefty dose of skepticism.”

Disinformation payoff

To some extent, the repeated warnings about Russian-supported outlets like RT and Sputnik have paid off, at least when it comes to this month’s presidential election.

“They (RT and Sputnik) aren’t prominent domains in any of the analyses that we’ve done on false narratives of voter fraud,” Kate Starbird, a University of Washington professor and lead researcher with the Election Integrity Partnership, told VOA via email.

“They do sometimes amplify disinformation that is already spreading,” she added. “But they typically come in late and rarely change the trajectory of that disinformation.”

Some intelligence officials and researchers warn, though, that for now, that could very well be enough.

“You still see people sharing their (Russian) content in America,” said Clint Watts, a former FBI special agent who has been studying Russian disinformation efforts for years. “The reach of Russian news inside the U.S. … is exponentially higher than in other countries. So, they can see a return on it.”

Redfish red herring

To help grow that return even more, and to avoid labels that identify the content as Russian, outlets like RT and Sputnik have also begun pushing content through the social media accounts of some of their most popular hosts, added Watts, currently a non-resident fellow at the Alliance for Securing Democracy.

Then there is the Redfish channel on Instagram, which Watts said has allowed Russia to gain “significant traction.”

“They put up a heavy rotation on George Floyd protests, and that is now where you see Americans sharing it routinely, millions and millions of shares,” Watts told VOA. “They dramatically raised their profile, particularly with the political left in the United States and African Americans, who I’m convinced have no idea that Redfish is a Russian outfit.”

Far-right appeal

Russia is also finding ways to resonate with the far right.

According to the August report by the Global Engagement Center, Russian proxy websites like Canada’s Global Research website or the Russian-run Strategic Culture Foundation amplify conspiracy theories about subjects like the coronavirus.

Researchers like Watts say that propaganda then sometimes finds its way onto far-right websites such as ZeroHedge or The Duran, where it gets amplified again.

Another researcher warned that Russian efforts are also resonating with far-right conspiracy theorists, some of whom will pick up propaganda from proxy sites, or more mainstream sources like RT.

“All of these Q(Anon)-driven accounts — they love the Russian stuff,” the researcher told VOA on the condition of anonymity, given the sensitivity of the work.

Into the mainstream

Not all Russian propaganda efforts circulate on the fringes of American politics. Some of the narratives hang around and are repeated often enough that they become difficult to ignore.

“So then, they can get somebody else from the American far right or far left to pick up on that story and then eventually snowball that so mainstream picks up on it … coopting the American media in a sense,” said Omelas’s CEO, Hu.

Other times, Russia’s influence peddlers have found their contributors thrust into the spotlight.

For example, on November 20, U.S. President Trump repeatedly retweeted Wayne Dupree, who regularly writes opinion pieces for RT.

Just days earlier in a RT opinion piece, Dupree slammed what he described as “the fraudulent and brazen behavior of these Democrats to destroy the election’s integrity.”

“They are all going to fall hard, along with the major news networks that have sought to brainwash the American people,” Dupree added. “The entire system is coming down, folks. Get ready.”

A number of researchers and U.S. counterintelligence officials say the incident falls into what has become an all-too familiar pattern.

In June, U.S. officials and lawmakers warned that RT purposefully courted outspoken, local U.S. police officers and union officials, attempting to use their reactions to protests sweeping across the country to further inflame tensions.

“They know they no longer need to do their own work,” National Counterintelligence and Security Center Director William Evanina told Hearst Television in October.

“They’re now taking U.S. citizens’ information, and they are taking it and amplifying it,” he said. “Whether it be conspiracy theorists or legitimate folks who have wrong information, they get amplified consistently.”